Prompt Images

We all have our guilty pleasures. When I was growing up, my mother used to tape soap operas to watch when she came home from work. I remember snickering at how devoted she was to some of the storylines—that is, until I started watching them with her. The over-the-top drama, ludicrous shenanigans, and characters that were caricatures of themselves had an outlandish appeal to my otherwise suburban, white-bread upbringing.

But that was then. Now, Americans’ guilty pleasure is politics, where half of us elect reality TV stars to be president while the other half dream wistfully of (impossible) presidential impeachment. It’s not going to happen, folks—as the saying goes, impeachment is political, not legal.

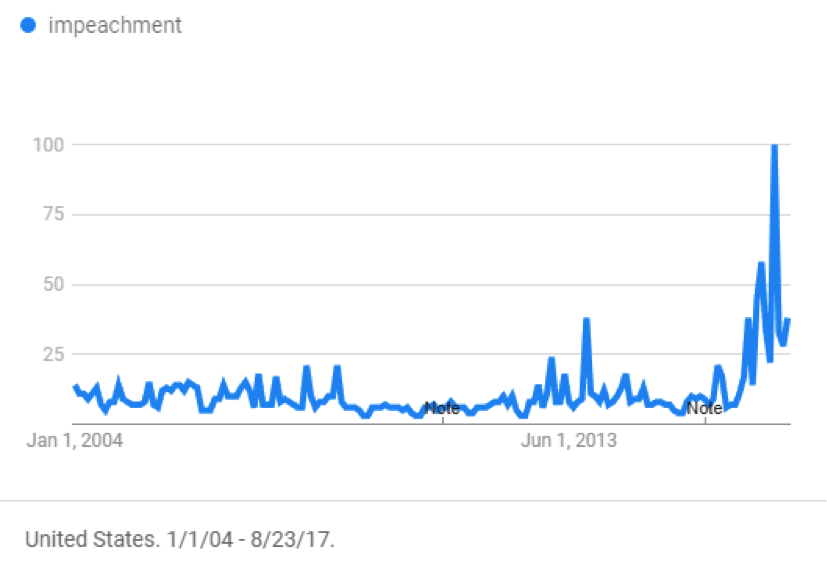

But that doesn’t stop America from daydreaming about impeachment. Google shows it’s been on our minds recently:

Data from Google Trends. Anyone know what happened in October 2013?

Impeachments are the highest form of modern drama.

They are a righteous crusade for justice if you’re the party out of power, a rallying resistance against witch hunts if you’re the party in power.

They also happen to provide great sound bites.

Congress never formally impeached President Richard Nixon—as he resigned before the House of Representatives could complete this step—but as the Watergate scandal unfolded, his defiant insistence that “I am not a crook” became a staple of U.S. History classes.

Happening as it did before the age of television, President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment in 1868 does not have any YouTube clips to review. But history records Representative William D. Kelley of Philadelphia insisting, “Sir, the bloody and untilled fields of the ten unreconstructed States, the unsheeted ghosts of the two thousand murdered negroes in Texas, cry, if the dead ever evoke vengeance, for the punishment of Andrew Johnson.”

As our most recent example, we have the impeachment of President William Clinton. The sound bite that came to define that event was his infamous public declaration, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.” Here, Clinton argued that since he and Monica Lewinsky did not have sexual intercourse, they did not have “sexual relations.”

But Clinton uttered another well-known line during the proceedings, one with a more linguistic twist. During testimony to a grand jury, Clinton said:

“That depends upon what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

The reaction from conservative circles was predictably outraged. The meaning of the word “is?” Either something is, or it is not. How ridiculous can you get at dodging a question?

It turns out there’s something to Clinton’s statement. “Is” seems like a simple word. Two letters, seemingly straightforward. But let’s take a look behind the scenes.

Verbs’ Vibrant Variety

In English, the word “is” is a verb. As Schoolhouse Rock1 tells us, verbs express states of action, being, or states of being. And “is” is a verb of being. In fact, it’s part of maybe the most basic verb: the verb “to be.”

“To be or not to be. That is the question…”

With this line, Shakespeare’s Hamlet begins his famous soliloquy about the worth of human existence. And the opening words, “to be,” are an example of the infinitive form of a verb. You can recognize these forms in English because they almost always show up as “to <verb>.”2

But as famous as Hamlet’s speech is, its subject “to be” is pretty boring and basic. Infinitives might be verbs, but they don’t generally convey a lot of information. They tend to represent only the bare-bones concept of a word. The verb “to dance” in the sentence “They want to dance” is just there to convey the concept of dancing. There’s no actual dancing going on in this sentence—in fact, the sentence is actually about someone wanting something.

If verbs were cars, infinitives would be the most basic model: no trim, manual windows, manual transmission. (And definitely no CarPlay.) But when we use verbs in everyday language, we usually don’t settle for the base model. We want the dealer add-ons!

The Meaning Of “Is”

The most obvious verb add-ons happen when we take a verb out of the infinitive form and use it as the main verb of a sentence. When we do this, we sometimes change the verb into different forms based on the subject of the sentence. This is why we say “I run quickly” but “He runs slowly.” The extra -s happens whenever the person talking is referring to a single person who is neither the speaker nor in the audience. In other words, the sentence is about a single third person—and that’s why English teachers say that “runs” is the “third person singular” form of the verb “to run.”

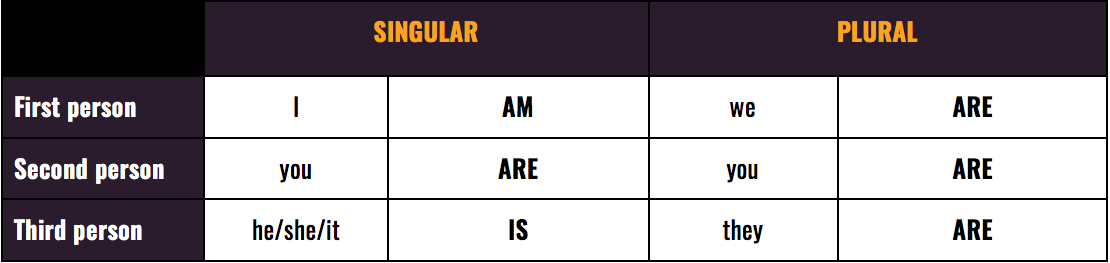

Most English verbs don’t change much when we make them agree with the subjects of their sentences. “To be” is a bit of an exception. You may recognize the structure below from learning verbs in foreign language classes, which generally have a larger number of verb forms than English, but here’s the conjugation for “to be:”

So the meaning of “is?” It’s just what you use when your subject is he/she/it—or a person’s name—and your verb is “to be.” It expresses a state of being about someone who is not present.

It’s Getting a Little Tense In Here

We have our first verb add-on. But there’s more to verbs than just subject agreement. Three other common verb add-ons are tense, aspect, and mood:

- Tense tells us when the action indicated by the verb is happening. In English, it’s the difference between “I eat” (present tense) and “I ate” (past tense).

- Aspect tells us about how the verb extends in time. It gives us information on whether the action is completed or still continuing in the time frame of the sentence. In English, an example is “I ate a large dinner yesterday” versus “I was eating dinner when the phone rang.” In the first sentence, the eating is finished but in the second, it’s still going on.

- Mood is an expression of the speaker’s attitude. A sentence where the speaker is stating a fact or asking a question uses different verb forms from someone giving commands. Compare “Duke is a good boy,” to “Duke, be a good boy!”

English is relatively different from a lot of other languages in how it expresses tense, aspect, and mood. Anyone who has studied foreign languages may remember having to learn lots of different forms of verbs. But in English, we don’t have such a large number of verb forms. Instead, we express many tenses, aspects, and moods by dropping the “to” from the infinitive and then adding other words.

Check out various how various tenses, aspects, and moods look for even a basic, easy-to-understand verb like “to walk:”

- I walk (to school).

- I walked (to school yesterday).

- I will walk (to school tomorrow).

- I am walking (to school right now).

- I had walked (to school by the time the storm started).

- I was walking (to school when the bus showed up at home).

- I have been walking (to school since I started exercising more).

- I would walk (to school every Friday).

- I would have walked (to school if I knew you were walking as well).

- I will have been walking (to school for a total of 4 years after tomorrow).

- I would have been walking (to school if you had come to my house yesterday morning looking for me).

- I do walk (to school as a general rule).

- I have walked (to school for nearly every day this month).

This doesn’t usually cause any confusion with verbs like “to walk.” Yet notice that we add in forms of “to be” and “to have” to get these phrases. You may remember them from elementary school as “helping verbs” because they help the main verb do its job.

To look a little more closely, “I am walking” suggests that at some point I will stop walking. “I walk” has a more open-ended flair to it; perhaps I don’t own a car so I always have to do it, or perhaps I’m making a statement about exercise and walking is important to who I am.

But if the main verb we’re actually using in our sentence is “to be,” then things often get messy and we tend to delete the helping verb. This happens especially with constructions of aspect, or completion in time. You’d never hear someone saying “I am being mad” to indicate they’re mad at the moment, but probably not forever. Instead, they’d say “I am mad,” even though that has that same open-ended flair as “I walk.”

So “is” has a second meaning! It can convey aspect in English; “he is walking” indicates that the action “walk” is a continuous action in the present time.

Three’s A Crowd

A third complication with the “is” issue is that English often uses “to be” for double duty as a placeholder. If someone asks about the weather, we might say “It’s raining.” But consider how “it is red” is different from “it is raining.” Some object is red in the first sentence, but … what exactly is “it” referring to? The rain? The rain isn’t raining, the rain just… is.

But we can’t just say “Raining,” as a sentence.3 We need something to fill in the blanks of subject and verb.

So in this case, “it” and “is” get brought in to make a complete English statement. You can see the same thing with “There is” or “There are:” “There are two kinds of people” just means “Two kinds of people exist.” Just like the rain is existing in “It’s raining.”

So in this sense, there’s a third meaning for “is:” to flesh out a statement or assertion about the existence of an object or concept.

Let’s Talk About Sex, Baby

Back to Clinton’s “That depends upon what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.” Which of the three meanings are we even talking about here?

Let’s check out the context of the statement. The President was responding to a question about whether or not his lawyer had earlier made a false statement when saying that Lewinsky was claiming “there is absolutely no sex of any kind in any manner, shape or form” with Clinton.

The prosecutor’s question focused on the third meaning of “is,” one that suggests existence. Since there had been sexual shenanigans at some point, the statement “there is no sex of any kind” was false. But Clinton argued along the lines of the first and second meanings. Since the relationship between himself and Lewinsky had ended by the time the question came up, “there is no sex” is true. “There was no sex” is not true, but according to Clinton’s interpretation that’s not the same question.

In fact, the very next sentence Clinton said was:

“If is means is, and never has been, that’s one thing. If it means, there is none, that was a completely true statement.”

So believe it or not, he’s not wrong to bring up the meaning of the word “is.” Of course, it’s definitely splitting hairs as politicians are wont to do, but you could say there’s a real argument there. Whether or not it’s a good one to make, or one that endeared him to his opponents, is another story. Clinton would eventually be impeached (but not removed from office) due to other statements he made that showed he lied under oath, but he was at least right that “is” is not so simple.

All of which goes to show that presidents can know more about the intricacies of language than we give them credit for. I do hope you’ll excuse me for not holding my breath for the current occupant of the office, though.4

1 “Verb: That’s what’s happening!” may be the single most profound song lyric I’ve ever heard in an educational song.

2 Many other familiar languages have infinitive forms that end in specific letters, a fact many high school or college foreign language students probably remember. French infinitives almost all end in -er, -re, or -ir, Italian has its -are, -ere, and -ire, while Russian’s end in -ТЬ, -ЧЬ, and -ТИ.

3 At least not in English. The Greek sentence “Βρέχει” for “It’s raining” doesn’t have a subject, because Greek (and many other languages) doesn’t require subject pronouns all the time.

4 Trump may be a great many things, but he’s certainly not The Great Communicator. Check out what results when someone took up an online challenge to diagram one of Trump’s characteristic ramblings.