Prompt Images

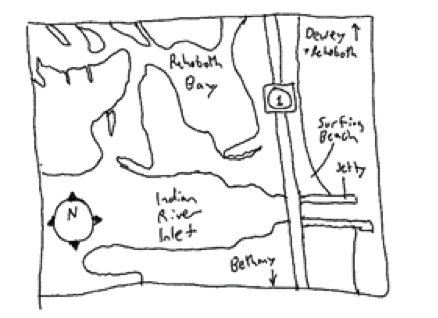

On a recent Thursday afternoon, I jumped in my car and drove south on Delaware State Route 1 out of Rehoboth Beach, through Dewey, and across Delaware Seashore State Park to the Indian River Inlet, the meeting point among the Rehoboth Bay, the Indian River Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean.

On that Thursday afternoon it would have been almost impossible for me to be unhappy, because I was going surfing.

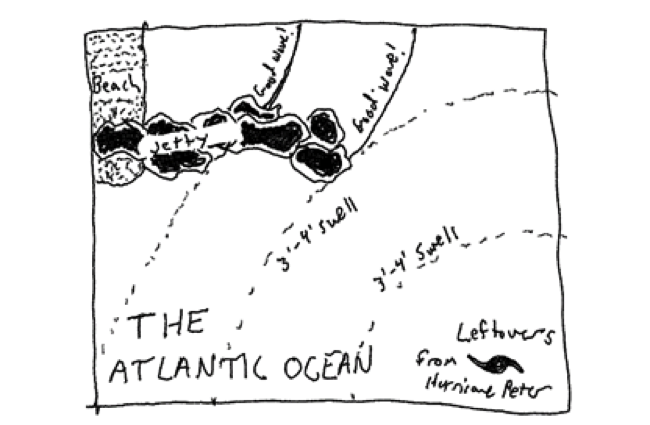

Surfers need good waves, and good waves need a particular kind of weather. On that Thursday afternoon, the weather was more or less perfect for waves and for surfing. Out in the middle of the Atlantic, the remnants of Hurricane Peter had whipped up a 3- to 4-foot East-Southeast swell. That swell traveled hundreds of miles across the ocean, and the part of it that was of interest to me was wrapping itself around the Jetty on the north end of the inlet before cresting and falling in perfectly peeling shore break.

The jetty is what makes the Indian River Inlet a surfing location. In fact, the jetty is what makes the Inlet into any kind of location at all. Without the jetty— which is composed of giant hunks of steel and rock that form a semi-submerged line pointing due east out into the ocean—there would be nothing heavy enough to hold the Inlet in place. Before the federal government installed the jetty in 1939, the mouth of Inlet had drifted north and south along the coastline as waves and wind pushed the unmoored sand. It had been impossible to travel along the shoreline between Bethany Beach to the south and Rehoboth Beach to the north. You had to go around.

I was lucky to get such perfect waves. The local online surf forecast had pooh-poohed the day’s prospects, wrongly predicting continued easterly winds that would chop up and ruin the waves. Whether this was deliberate misdirection to keep out-of-towners away from ideal conditions or an honest error in forecasting, I have no way of saying. I do know for sure that the absolute reverse was true.

Here’s what’s great about a jetty: In addition to whatever maritime and industrial purposes it is intended to serve, it also cleans up the surf coming in from anywhere south of the beach and shelters the waves from southern crosswinds. On this recent Thursday, there was basically no storm activity out of the northeast. The easterly winds, which earlier in the week had jumbled the waves on top of each other, had died down and shifted to come from the west. That’s what you want. A westerly wind gently pushes against incoming waves, slowing them and making them stand tall as they break, preserving the face where surfers can ride.

On top of all that, the morning’s rain was clearing up—good waves and late summer sun just as the 9 to 5 work day was ending.

Arriving over the dunes, I exchanged pleasantries with some college-aged kids in town for the week and set my stuff near them, then hopped in and paddled out to a place in the lineup where I could expect to catch some waves but would not annoy the local surfers. About 30 surfers – more than I’d ever seen at this spot – bobbed in the water, waiting for the right wave.

I was careful at first. When visiting someone else’s surf break it’s important not to be a bother.

The hierarchy of a surf lineup is its own political sorting system. Locals typically sit on the spots where the biggest and best waves usually break. Among the locals, the best surfer—or the most intimidating one—will usually be in the absolute best spot. Etiquette dictates whoever catches the wave closest to its peak has the right of way. Other surfers must defer by pulling back and waiting for another opportunity.

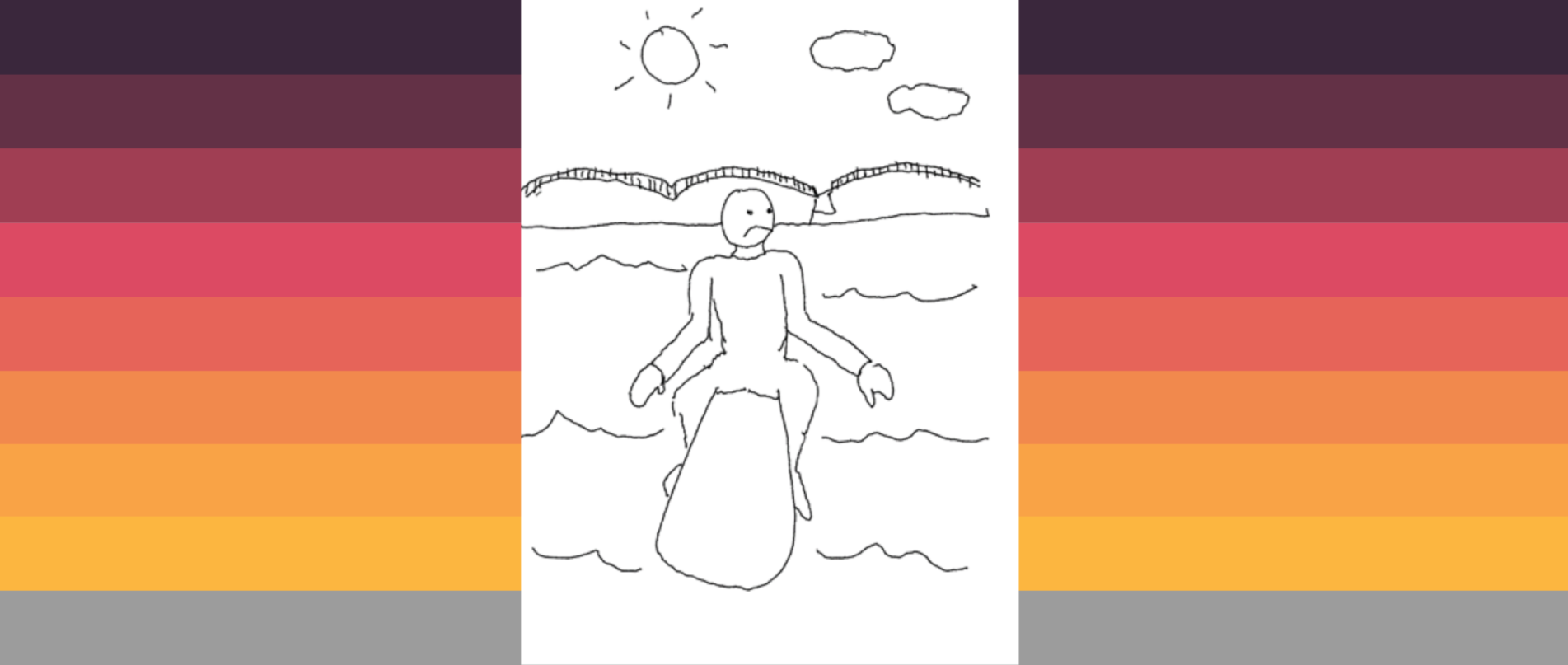

Etiquette further dictates that outsiders defer to locals. So it’s standard for someone in my position—a vacationer from Washington, D.C. on a rented foam board typically used by beginners—to sit on the outside of the lineup, away from where the good waves were peaking, and hope to get lucky, either that a good wave would happen to peak near me or that all the surfers ahead of me would miss out on a good one and I’d have it to myself.

Floating, waiting and watching, I felt the way Jack Kerouac described Charlie Parker, like I was the perfect musician waiting to play. I imagined the expression on my face:

as calm, beautiful and profound

As the image of the Buddha

Represented in the East–the lidded eyes

The expression that says: all is well

I was surprised and annoyed to see nothing close to this expression on any other surfer in the lineup. Instead I saw the stoic, solitary irritation of commuters on a subway platform, waiting for their rides. The water was almost lukewarm, probably 72 degrees. Every other surfer was wearing a black wetsuit. “Seems like kind of a warm day for a wetsuit,” I thought.

The king of the hangdog commuters was also one of the most skilled surfers in the lineup, probably also a local.

He had a “real” surfboard made of fiberglass, painted a beautiful red with a cream-colored diamond toward the nose.

He happened to be taking off on a wave just as I was paddling out. I saw he could carve the entire face of a wave, shifting his balance right, left, fore, and aft, like a joystick mounted to the board. He carved a cutback, executing a hairpin style turn from the top of the wave all the way down toward its outer limit and then sharply back, nearly to the foamy soup before resuming his original direction. I barely made it out of his way as I paddled out and over his wave.

“Hey nice turn,” I said to him.

He looked back at me and said, “Would’ve been better if you stayed out of the way.”

I firmly believe everyone is entitled to experience the world on their own terms, with one major exception: This surfer should enjoy himself, not act like a sour ass on the most perfect of all days.

How could this guy not be having a good time?

There are many possible reasons—surfing is tiring and requires intense concentration— but two candidates stand out to me as the most likely.

I imagine this surfer was one of those people who is more interested in improving his surfing than he is in experiencing it. Each wave is a practice rep—for footwork, to try a new trick, to further master the mechanicals that go into excellent surfing — an approach I see as foolish.

I believe technical mastery without joy is useless.

I believe joy to be the necessary input to all life’s activities, but especially the fun ones. I believe technical mastery is a red herring, and I believe this person has fallen for it.

The second likely reason this surfer was not having a good time was that he had, at some point, become entitled, and entitlement had robbed him of joy. As the best surfer on the beach, he believes himself to deserve a clear path, free of inferior surfers who might jeopardize his wave or worse—injure him and his delicate fiberglass surfboard. King Sad Surfer didn’t want to share his beach with anyone and expected better manners from beginner surfers who either didn’t know enough or weren’t good enough to stay out of his way.

“This guy is a little too serious,” I thought.

Neither skill nor experience seem to protect a surfer from feeling miserable doing what they’re supposed to love

Often the best surfer in the lineup looks preoccupied, almost disappointed.

Being the best surfer at the Indian River Inlet in Southern Delaware is no grand title, if we’re being honest. It does mean you can carve waves with confidence, maybe slap the board against the lip of the wave as it’s cresting and free falling back down onto the foam. In other words being the best surfer at the Indian River Inlet in Southern Delaware means the ability to surf with some measure of control and power. A reasonably athletic person who makes surfing their primary hobby will most likely become the best surfer at the Indian River Inlet within a couple of years.

The problem for surfers of this guy’s skill level at spots like the Indian River Inlet is: The spot is not intimidating on days when the waves are good. People drive in from Dover, Wilmington, Annapolis, even places in Virginia to catch the Inlet on a good, clean day. When the waves are not enormous but the surf is breaking right, the spot floods with beginners. Even worse, a beginner can surf pretty well in perfect conditions, eroding the skill advantage and status afforded a local hero.

I am not a local hero, but I am a happy surfer.

And you might be surprised to find out that being a happy surfer is not exactly common. About ten years ago I was attending business school at the University of California San Diego. One of my friends there, Barrett, was a lifelong California surfer. He grew up in Oxnard, attended undergrad at UC Santa Cruz, and enrolled at UCSD shortly thereafter.

One day we were spitballing corny business ideas at Barrett’s apartment in Pacific Beach, San Diego’s party beach town. I came up with the idea for a tuxedo-print wetsuit so surfers could look hilariously formal as they rode waves.

Barrett shut me down right away. “No way.” He looked sincerely offended.

“Oh, come on, it’s a fun idea,” I said.

“If you paddle out in Santa Cruz wearing a tuxedo wetsuit they’ll throw you out of the water,” Barrett said. Surfing isn’t about drawing attention to yourself. You have to wear a black wetsuit—no designs, no nothing. Only Kelly Slater could get away with wearing a different wetsuit, and even then it was just a white wetsuit, and even then other surfers like Andy Irons hated Slater for it.

There was no refining this idea: Barrett was completely serious and adamant that wetsuits must remain pure and black. (Whether Barrett likes it or not you can buy a tuxedo print wetsuit online today if you want to. It looks terrible. We were both right.)

I went on from business school to a career in financial news and the investment industry. I wisely (I think) avoided self-parodic action sports business ideas. But I resolved from that conversation on never to take surfing as cosmetically seriously as Barrett had. Which is partly why, on that recent perfect Thursday afternoon, I was shirtless on my surfboard, wearing royal blue swim trunks with a pattern of watermelons sprinkled all over them. They look like novelty boxer shorts a middle-aged dad with two kids (which is what I am) would wear.

I had a great time chatting up the other surfers who weren’t quite as good as our friend, the Surf King. I lost count of the number of waves I caught. I displayed good manners, staying off other surfers’ waves.

Surfers do not have a reputation for being overly articulate.

I think that is because a lot of our brains genuinely have been baked by the sun, but I also think it’s because the experience of riding a wave on a surfboard is nearly indescribable. It’s not our fault we don’t have anything intelligent to say about it.

Videos of surfers on television or YouTube make it look much more active than it really is. Once you’ve paddled past the breaking waves on a good day, a lot of what you’re doing is sitting on a board, looking toward the horizon for the type of faraway ripple that’s going to assume proper shape as it approaches. Many waves will remain too flat, looking like the standard normal bell curves you find in statistics textbooks, failing to muster the power to carry a surfer to shore. On most days a surfer has to sit for minutes at a time, emptyheaded or chatting with others in the lineup, waiting as these gentle rollers loll past.

The ones that are going to rise up and break, the ones that are fully powered, give a hint of their intentions a matter of seconds beforehand.

They show a face, coming up sharper and more in focus, like concrete ramps that capture more sunlight and seem to glow slightly before the spittle of foam forms at their tops and they start to gnarl, first at their pyramidal peak and then off towards their sides, north and south to the flat water below them. When you, seated on your board, see that face and that glinting period, you shift your weight to aft, lifting the nose out of the water and twirling around to face the shore. You paddle Australian Crawl style, making your deltoids burn and arching your back, feeling the pull on your lats as each hand catches a grip on the water below you, and you propel yourself forward until you “take off”—the moment the wave picks you up.

“Take off” is a correct metaphor. Being on a surfboard when a wave agrees to grab it and bring it toward the shore for you feels how you might feel if you were lying prone on the floor of a 747 right at takeoff. The earth’s gravity shifts from below you to slightly behind you, and you get a feeling of sinking backward into the arms of the wave as it starts its push. Because it is so thrilling to feel your Newtonian relationship with the planet seem to suddenly adjust (people who have been in a minor earthquake will relate to it), many beginning surfers overreact to the signal and begin a self-defeating attempt to scramble to their feet. In truth, once the takeoff begins you need to take a few more strokes, then pause and gather yourself together before you rise to your feet in as decisive a motion as your quick-twitch fibers will permit you.

With that accomplished, if you can keep a focus on what you’re really out there for, and keep yourself from wondering whether some inferior surfer might drop in on your wave, your consciousness will fade to the gray near-black of a 1960s TV set whose plug has just been yanked from the wall and the last bit of electricity fades from its vacuum tube. When it returns, your visual field will be reduced to a hyphenated series of jumping strobe-lit shots—the wave ahead of you, the board beneath you, white water behind and an ever-changing incline of surface tension that in reality may only be the size of a folding table, but in that moment will somehow totally overwhelm the world around you.

Tunnel vision is inaccurate; your vision goes kaleidoscopic.

The section of the wave you’re on multiplies and envelopes you like the ceiling at a planetarium, replicating itself like a blue cascading series of chaotic stars. The only sounds I’ve really ever heard while on a wave are keens of excitement—my own or from other surfers.

Eventually the ride will end, and in that final moment for me, the memory almost inevitably self-destructs. I process the world verbally and not via tactile sensation anyway, so the gravity-shifting kaleidoscope resists my taxonomic and archival systems, and I’m left with only a sensation that something astounding just happened to me, but now I am back in the ocean as it was previously constructed. The horizon is once again a flat, blue, shifting, rolling line back out there, away from shore, and I’m back on my belly, my watermelon trunks adhering to my foamy rental board, smiling as big as I can at The Surf King as he grunts and groans his way back to his spot in the center of the lineup.