Prompt Images

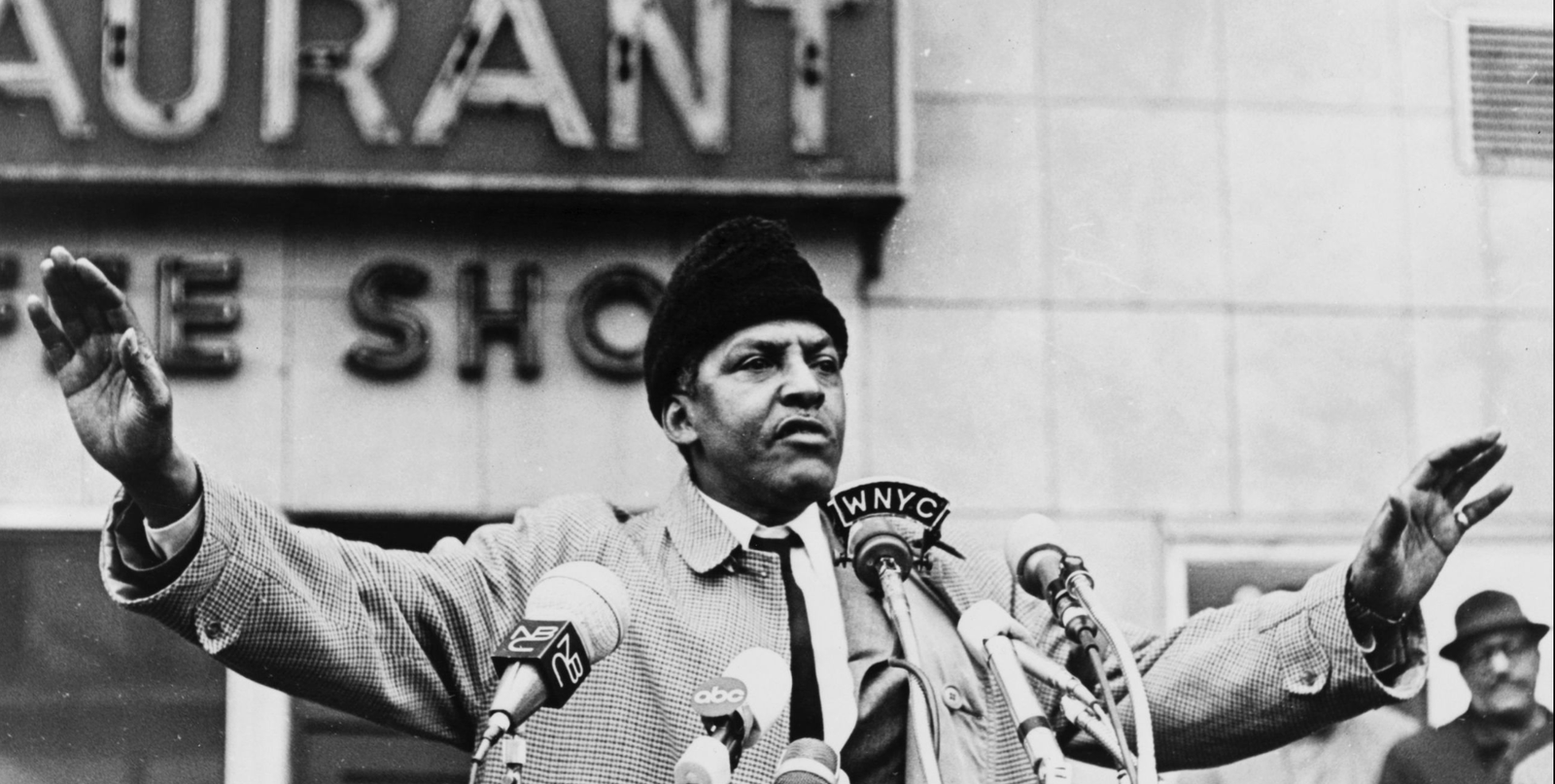

Bayard Rustin was a Swiss Army knife for justice, a jack of all trades for morality, a catalyzing spark, and a holder of the Black Radical Tradition. This brother worked with so many of the Black titans, from Ella Baker to Martin King, A. Phillip Randolph, and so many more.

A lead architect of the 1960s Civil Rights epoch, Rustin was involved and/or in coordination with the likes of Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee. He was also the lead organizer and trainer for the epochal Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1956, who basically introduced Martin King to Gandhian nonviolence tactics at the same time.

Rustin stood with Japanese Americans to protect their property in California while they were imprisoned in internment camps. This brave action vindicated Baker’s sage words:

“Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind.”

All said, Rustin is most known for his role in visualizing, developing, and bringing to life one of the most ubiquitous moments in U.S. history—the 1963 March on Washington, an event that still acts as a harbinger for social uprisings against lasting oppressions.

Moreover, Rustin faced more than just the oppression of a Black man. Though lesser known and, until recently, seldom discussed is Rustin’s sexual orientation and how this impacted his work and his relationships with those he worked with.

Being gay in the 1960s was no easy way to live. –

In far too many cases, people were not allowed to live and love openly. Being gay, Black, and outspoken (or, ya know, “uppity”) against a system of white supremacy in the 1960s was sheer masochism. For Rustin, the execrable treatment he received for being gay was not just elicited by anti-Black lawmakers like Strom Thurman, but also by his own Black people.

During one disagreement over organizing an event, Adam Clayton Powell Jr.—a civil rights activist and the first Black Congressman from New York—threatened to leak false reports to the press about a secret affair between Dr. King and Rustin. And for all the planning, organizing, and leadership he demonstrated in making the 1963 March on Washington a reality, NAACP Chairman, Roy Wilkins, demanded Rustin not be publicly recognized for his efforts, stating, “This march is of such importance that we must not put a person of his liabilities at the head.” (That’s literally what I meant when I wrote a piece on what I call paradoxical osmosis.)

Rustin’s life and his corpus of work are beacons of perseverance and lessons of the necessary introspection and cogitation we must undertake as a Black community. We have MUCH work to do as pertains to seeing the full humanity and right to freedom rights for Black LGBTQIA peoples. How the fuck can we even pretend that we are not being specious when we say, “Black Lives Matter, if we don’t mean ALL Black lives? Moreover, we as Black folk must not rest until we collectively address and dismantle the reality of Trans Black women subjected to a daily culture of slaughter that contributes to a life expectancy for them of less than 35 years.

Bayard Rustin was forced too many times to hide who he was.

Homophobic attitudes pillaged him of the freedom to be his full self, and the invisibilization he endured was, and remains, derelict of morality. While necessary to the successes of the 1960s Civil Rights epoch, the ghosts of flawed, patriarchal, and, at times, toxic Black men haunt us to this day.

Yet this is why Rustin is also a hero. He forces us to embrace a past that is traumatic, triggering, and tumultuous, while inviting us to emerge better, because we must. He is Pride and he makes me proud AF to be Black.