Prompt Images

Colin Kaepernick has been dubbed many things in the past year. Protester, attention-seeker, hero, entitled-millionaire, philanthropist, ingrate, communist, antwi-American, leader, scapegoat, lunatic, and son of a bitch.

But before Colin Kaepernick was any of those things, he was a football player. And no matter what you think the reason is for Colin Kaepernick’s current unemployment, it became official when he opted out of his contract with the San Francisco 49ers. That means he turned down a player option of $14.5 million dollars to stay with the 49ers for 2017.

Before passing any judgments on his decision, note that the team has since admitted that it would have terminated his contract regardless. And since NFL contracts are non-guaranteed, Kaepernick would have still lost that money and his roster spot.

But what if Colin Kaepernick hadn’t terminated his contract?

How did that decision change the conversation around sports in 2017? How has it changed politics? And how has it changed the intersection of the two?

Had he accepted his contract status and stayed with the 49ers, Kaepernick says he would have stood for the anthem this year. In an offseason filled with charity and goodwill gestures, Kaepernick seems to have grasped that extreme actions alienate the masses, and had evolved his mission accordingly.

While the NFL has successfully kept Kaepernick off the field, it not kept his spirit out of the game. Kneeling during the anthem has continued despite persistent, threatening, and combative requests—by the president, fans, and owners—to give up their protest and stand. And for those who oppose them, perhaps the continuing protests sting more without Kaepernick because they have new life, new faces, and more staying power. Because when a river is obstructed, the water does not simply stop; it finds a new direction to surge.

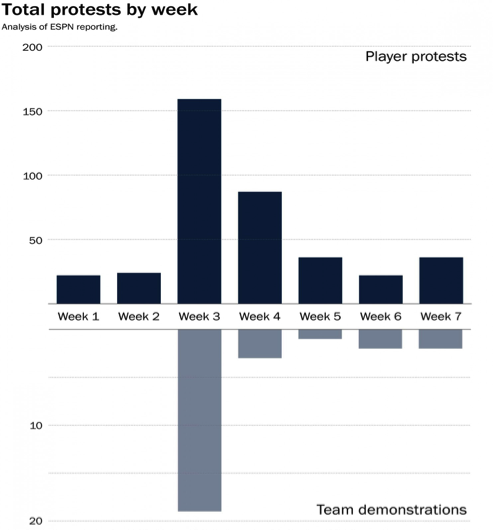

The groundswell for Kaepernick’s opposition came to a head before week three of the NFL season, when the president entered the fray. At a September 23rd rally in Huntsville, Alabama, Trump referred to players as sons of bitches, and told rally goers that, if up to him, he would fire any player who disrespected the flag.

Trump’s suggestion that other players should be fired and that their first amendment rights were a point of debate, forged the battle lines for a major conflict in the world of sports, beyond just the NFL.

LeBron James tweeted “U Bum” at Donald Trump. Steph Curry publicly announced that he would not go to the White House for the Warriors championship celebration. Trump doubled-down on his SOB comments, reiterating that protesters had no place in the league. NFL players across the league took to a knee in extreme numbers, sometimes even joined by team owners. Entire teams stayed in the locker room for the anthem. Even NFL commissioner, Roger Goodell, spoke on behalf of the players.

Many teams had players-only meetings, making group decisions to stand or kneel. Some owners sided with the First Amendment and their players’ freedom to peacefully protest, while others threatened their teams with benchings or worse. Jerry Jones knelt, arm-in-arm with his players before the anthem, to choruses of boos from fans. Same would go for the Ravens, as their own fans showered them with boos. Fans boycotted watching games on TV and the ratings fell.

Trump’s jingoistic comments set off a racially-charged Rube Goldberg machine.

But how different would the path have been if Colin Kaepernick was a member of the NFL?

Are athletes more inclined to protest in or because of Kaepernick’s absence? Or is it because they fear that a failure to protest leaves them as suckers and pawns? Basically, do they feel more driven by Kaepernick’s absence, out of fear or love? And where is Michael Scott to answer the difficult questions?

Colin Kaepernick’s continued on-field absence has forced many around the league into purposely uncomfortable conversations about race and equality. In October, the league hosted a players-owners summit to discuss the issues important to each side: activism, optics, and implications. The players asked Commissioner Goodell to dedicate a month of the season to activism, in the same way it does to cancer awareness or military appreciation (Salute to Service month is November).

But for every compromise or step to the middle, there is a giant step back. For example, when Houston Texans owner, Bob McNair, was quoted saying, “We can’t have the inmates running the prison,” regarding letting the players control the conversation. Perhaps it was a Freudian slip, or perhaps it was an off-color comment that he intended to stay behind closed doors. Regardless, his players threatened to walk out on practice and reportedly questioned playing that week.

Meanwhile, McNair and six other owners, along with the commissioner, are being investigated for collusion in keeping Kaepernick out of the league. They will be deposed and have to turn over their cell phones. Whether the league is found guilty or not, the NFL will find itself on trial in the court of public opinion, in conversations about keeping a vocal black athlete out of its league.

And then there is the whole actual football side of things.

The NFL’s on-field product is genuinely agreed to be as poor as it has ever been, especially among quarterbacks. The 49ers, Kaepernick’s former employer, won their first game this week (1-9), are last in the league in touchdown passes, and rank second-to-last in quarterback rating (a simple metric used to aggregate all of the things a QB can do into one, concise number).

Last year, Kaepernick was 17th in the league in quarterback rating (90.7), and had 16 touchdowns in 11 starts. Those numbers were middle-of-the-road, but Kaepernick’s critics point to the fact that he led the 49ers to a 1-10 record as a starter, without qualifying that the 49ers defensive was last in the league in yards allowed per game and last in the league in points allowed per game.

If Kaepernick repeated last season’s numbers this year, he would be the 16th best QB in the league, as the NFL and its owners are putting up with substantially less from many of their quarterbacks.

The Browns have flipped through quarterbacks this season like Donald Trump cycled through campaign managers, except that Trump ended up with one more win than the Browns currently have.

The Texans began the year starting a quarterback with no career touchdowns, who was benched after just one half. Additionally, the Texans recently signed Josh Johnson, who joins his 12th NFL team in 7 years, and has a career record of 0-5.

The Broncos, who boast all-pro receivers, have used two quarterbacks that both have more interceptions than touchdown passes. The Packers lost Aaron Rodgers mid-season, and when a reporter asked about signing Kaepernick, head coach Mike McCarthy blew up, suggesting Packers backup Brett Hundley was enough. Hundley, since taking over, is 0-3 with a QB rating in the mid-50s.

The league is also seeing career worsts from generally acceptable quarterbacks like Andy Dalton, Joe Flacco, Eli Manning, Jameis Winston, and Jay Cutler, who all rate below 88.

Normally we would understand that bad quarterback play is plausible, and that half of the quarterbacks will be below average. But with a skilled, dual-threat quarterback sitting at home, it’s hard not to see these foibles through a different set of senses.

And then we come back to the 49ers, who were and are so mired in quarterback wreckage, that they traded for presumed Tom Brady-successor Jimmy Garoppolo. Quarterbacks CJ Beathard and Brian Hoyer are respectively the 30th and 32nd best quarterbacks in the league, which also make them the fourth and second worst. Kaepernick’s absence, again, has felled dominoes across the league.

Would Kaepernick accepting the 49ers contract have changed any of this?

Kaepernick playing this season would not solve all of the NFL’s problems. If we’re to take Kaepernick at his word that he would have stood for the anthem, it would have created less tension between the players and league, and thus created less drama around the anthem. If we believe that fan boycotts of NFL games are more than just threats, Kaepernick’s presence come Sunday would absolutely have helped the league’s TV ratings. And least importantly, it surely would have earned the 49ers a few more wins.

But unlike the definitive, limited endings of a football game, Kaepernick’s exclusion from the league, leaves us with too many “what ifs.”