Prompt Images

For over a year, the tone and frequency of nationalist rhetoric has changed. This is most obvious in the candidacy, election, and inauguration of Donald Trump, who used his brand of nationalism to capture the hearts and minds of his supporters. Even in the wake of his missteps, his base has been rock solid, perhaps owing to the strength of their emotional connection with the president.

And what drives that connection? Identification: Trump represents who they are as individuals. Brash. Proud. Unapologetic. Traditional. AMERICAN.

But it is a mistake to attribute all of Trump’s strongest supporters to this group, as many pundits unfortunately have tried. Or to suggest that other groups—partisan or otherwise—don’t share nationalistic attitudes and beliefs. Unfortunately, many have tried to simplify American nationalism into preexisting categories divided by party affiliation, region, and other factors oft-described as “identity politics.” But this simplification ignores important nuances.

When it comes to American nationalism, the blade of Occam’s Razor is too dull to cut these groups into just Democrats and Republicans. We need a sharper instrument.

Enter scholars Bart Bonikowski and Paul DiMaggio, whose “Varieties of American Popular Nationalism” provides further refinement on American nationalism. The study goes beyond the overly simplified Republican versus Democrat or AMERICA FIRST versus BLAME AMERICA FIRST divisions.

Their analysis suggests a more robust classification into four distinct groups with varying intensity of and motivation for American nationalism. This is a crucial development, which begins to explain how nationalism impacts attitudes, voting behavior, and alliances.

The Four Types of American Nationalism

Analysis of survey data from 1996, 2004, and 2012 breaks American nationalism into four distinct groups: Ardent Nationalists, Restrictive Nationalists, Creedal Nationalists, and the Disengaged.

ARDENT NATIONALISTS (24 percent of respondents)

This group scores highest on every dimension of nationalism, including identification (feelings of closeness to the nation), pride (how proud they are to be American), and hubris (a resentful comparison between the United States and other countries). They also express a support for restrictive criteria in defining what makes others “truly American.”

So, ardent nationalists are your crackerjack “deplorables.” As expected, they are disproportionately white, male, Evangelical/Protestant, Southern, older, lower-income, and Republican. But even within this population, there is a segment of older, poorer Democrats, which just scratches the surface of a crucial takeaway from this report: Partisan politics are not what drive American nationalism.

RESTRICTIVE NATIONALISTS (38 percent of respondents)

More moderate than ardent nationalists are the largest group—restrictive nationalists. Almost 40 percent of respondents fit into this category of Americans who report “only moderate levels of national pride but defined being ‘truly American’ in particularly exclusionary ways,” according to Bonikowski and DiMaggio.

Demographically, restrictive nationalists are quite diverse but include overrepresentation from disadvantaged groups, including those of lower income and education, as well as women, African Americans, and Hispanics. The group also includes overrepresentation of political independents and those born in the United States. The authors of this study attribute some of the restrictive attitudes about what constitutes a “real American” to ressentiment, or suppressed frustration that turns inward toward other members of one’s own group. This is an interesting explanation, but would require additional research to confirm their hypothesis.

CREEDAL NATIONALISTS (22 percent of respondents)

Another more moderate and nuanced group are creedal nationalists who scored high on measures regarding their national pride, but who tend to be more inclusive of what it means to be American. As opposed to restrictive nationalists, this group is more welcoming to those who are not Christian or were not born in the U.S. for example, provided they follow the “American creed”—respecting the rule of law and U.S. institutions.

This group is another interesting demographic category, with disproportionate representation of those with higher levels of education and higher income (a mean income almost 40 percent higher than the next group). The group also includes overrepresentation from Republicans, those born outside the U.S., Jews and Cathloics, and those who reported their race as “other.” So, truly a complex mish-mosh of characters whose may be categorized as “the ideology of men and women for whom the American Dream has worked,” according to Bonikowski and DiMaggio.

THE DISENGAGED (17 percent of respondents)

The smallest group is on the other extreme, as far from ardent nationalism as we can find. This group “withheld the strongest endorsement of even the most widely held nationalist beliefs and sentiments, because they professed particularly low levels of pride in state institutions, and because they appeared to refrain from wholesale engagement with a national identity.”

This group includes an overrepresentation of younger, more educated, and less religious Americans. Racially, the group includes an overrepresentation of African-Americans and those who classify themselves as “other.” Regionally, it skews toward the Northeast and Pacific West. And, the disengaged report lower incomes, which is somewhat misleading, given their relatively young age compared to other groups (mean age of 38).

Electoral Implications

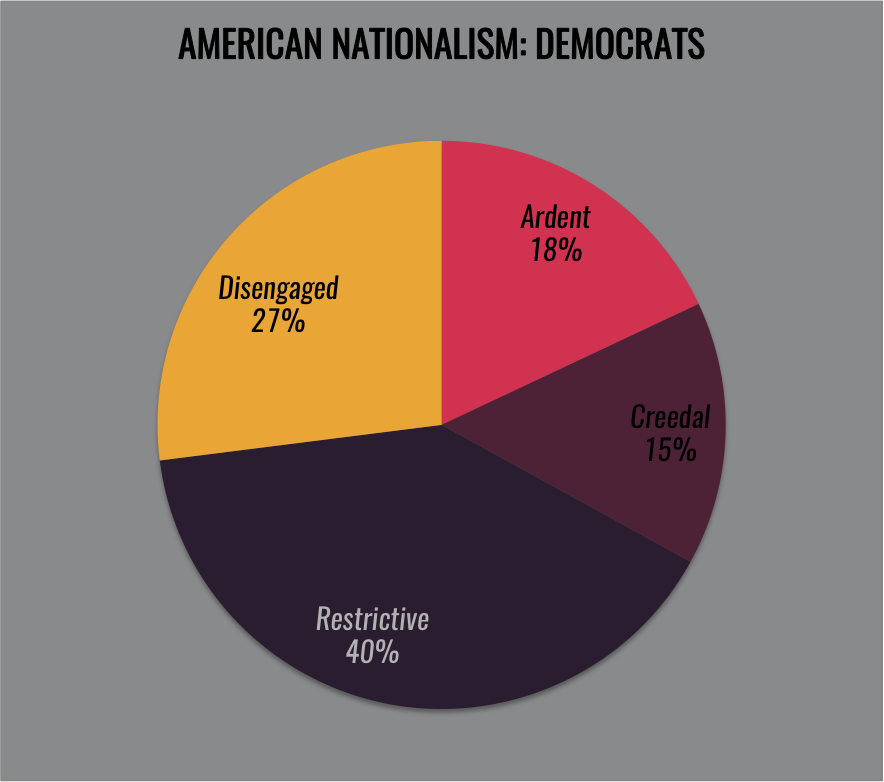

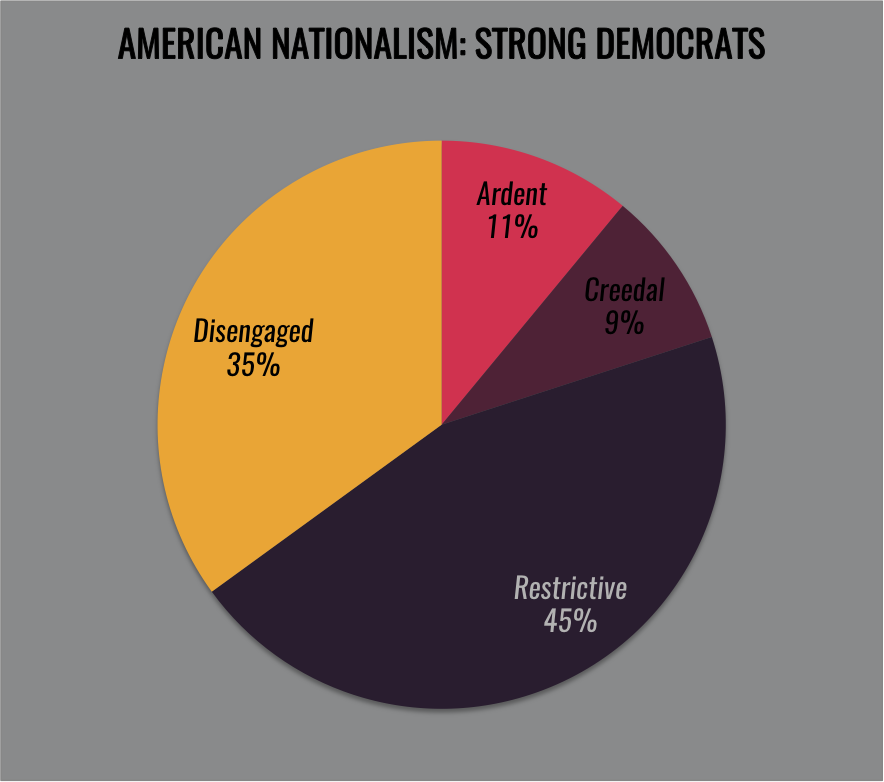

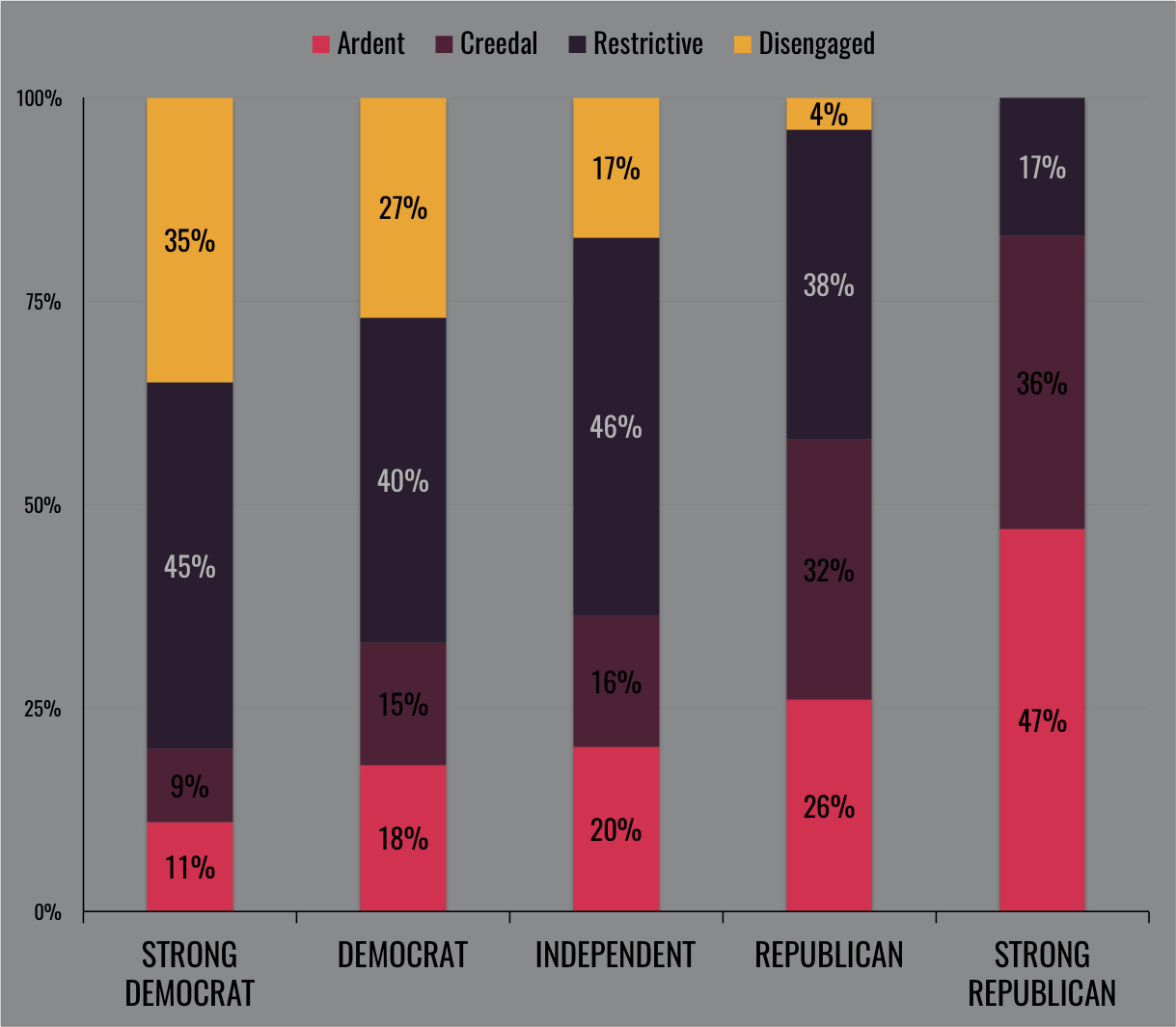

While many have falsely attributed nationalistic attitudes to the Republican Party, that generalization is both incomplete and inaccurate. As revealed in this study, and shown in the graphs below, “It is notable how little overlap we observe between nationalism and partisan position among [restrictive and creedal nationalists].”

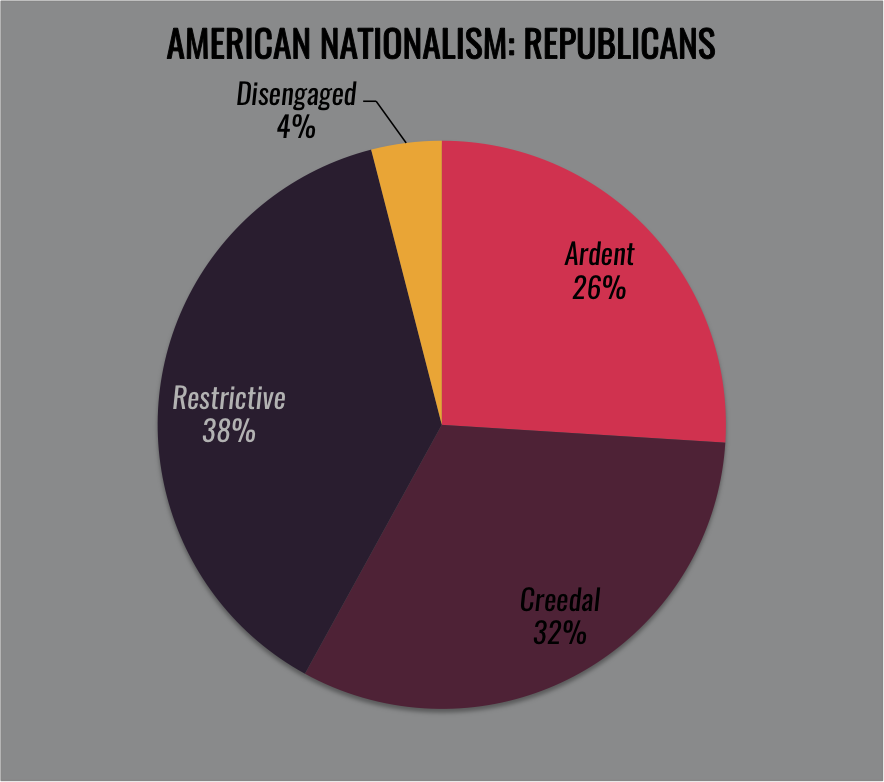

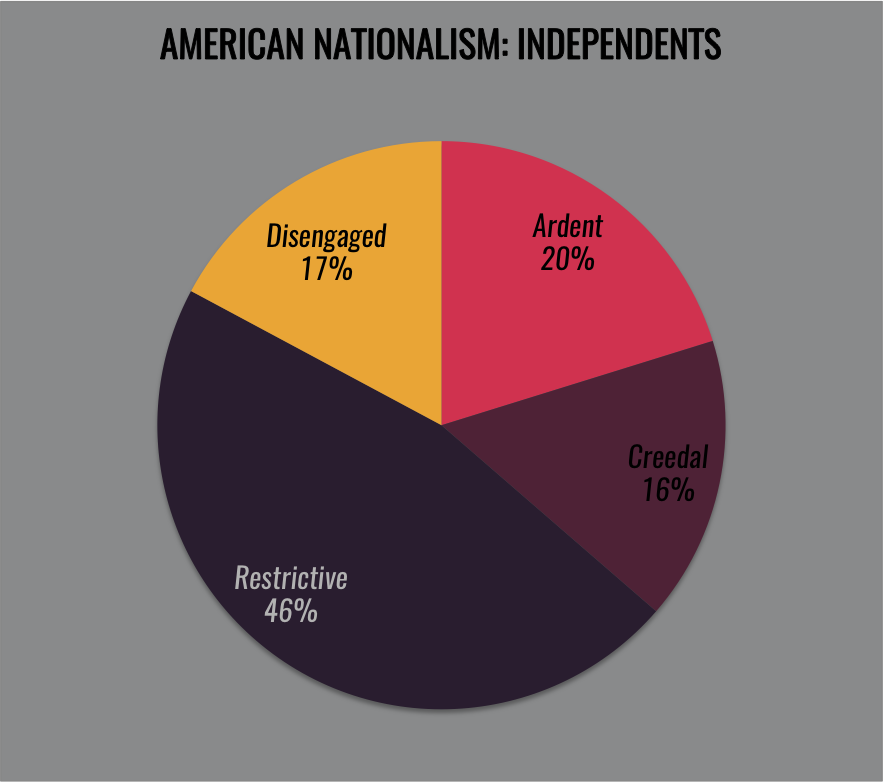

For example, the percentage of Democrats and Republicans classified as restrictive nationalists is quite similar (40 and 38 percent, respectively), with both Strong Democrats and Independents not far behind (45 and 46 percent, respectively).

Democrats and Independents are also quite similar when it comes to both ardent nationalism (18 and 20 percent, respectively) and creedal nationalism (15 and 16 percent, respectively).

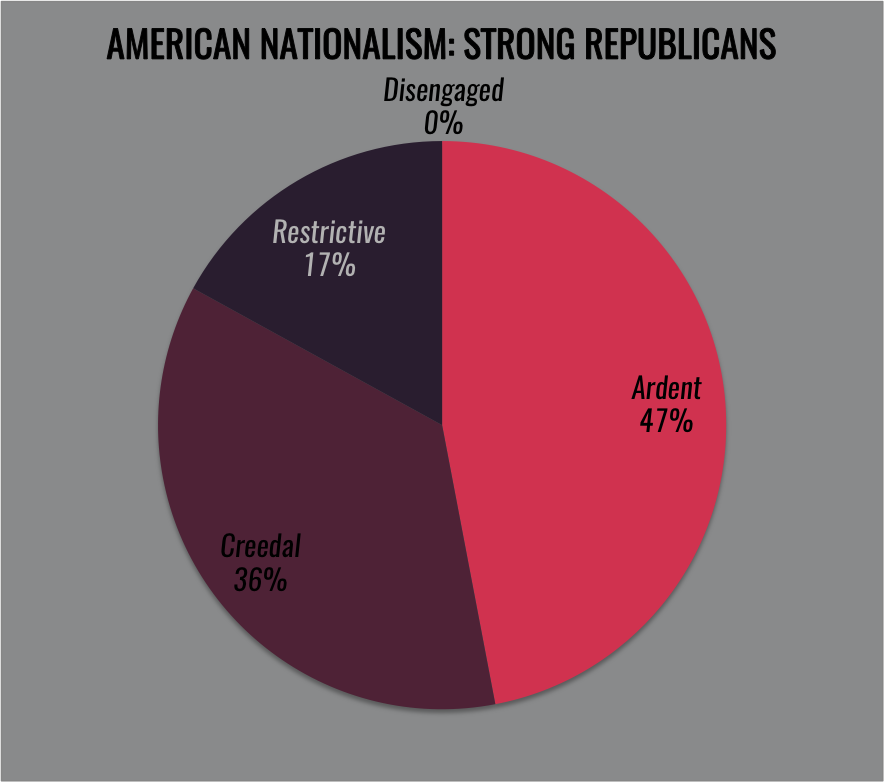

Perhaps the most notable partisan pattern is with Strong Republicans, which may explain why media pundits have focused so strongly on them. Notably, ardent nationalists account for almost half (47 percent) of Strong Republicans, which is nearly twice its incidence for Republicans (26 percent) and even more so than all other partisan categories. And a slice of pie is missing entirely from Strong Republicans, where 0 percent fall into the disengaged category.

This may be striking but should not distract from the main point. Moderate forms of American nationalism are significantly more prevalent AND felt by the majority of Americans.

So in the many calls for finding a unifying strategy and actually reaching American voters, it is essential to dig deeper into the various forms of American nationalism, to understand what drives these attitudes, what rhetoric resonates, and what policies will appeal to the vast majority of Americans who sit in the middle. This is just the beginning.