Prompt Images

I. Elon Musk Seems to Think So

Elon Musk, the founder of Space X and Tesla, believes “there’s a one in billions chance we are living in base reality.” By base reality, Musk means a reality that isn’t being itself simulated by some higher reality. In other words, Musk thinks it’s highly likely that we live in The Matrix.

He’s not the only person, by the way. It’s become quite fashionable among the science and tech cognoscenti to believe that we are living in a simulation. But where’s the evidence for this crazy idea?

II. A Proof That We Live In a Simulation

Before we start, I should clarify that I’m not actually going to prove that we definitely live in a simulation. What I’m going to prove is that it’s statistically speaking, extremely unlikely that we do not live in a simulation. Got it?

Here’s the proof:

1. The universe operates according to prescribed laws of physics (and chemistry, biology, sociology, etc.).

2. It’s feasible that one day in the future we could build a computer to simulate a little universe of our own, complete with laws of physics, chemistry, biology, etc. Said simulation could also include trees, animals, and people.

3. If we simulated a universe, it’s conceivable that said simulated universe could do the same and simulate a universe of its own. Also, if we simulate a single universe, why not simulate a couple hundred, or a couple hundred billion? Ditto for the universes we simulate.

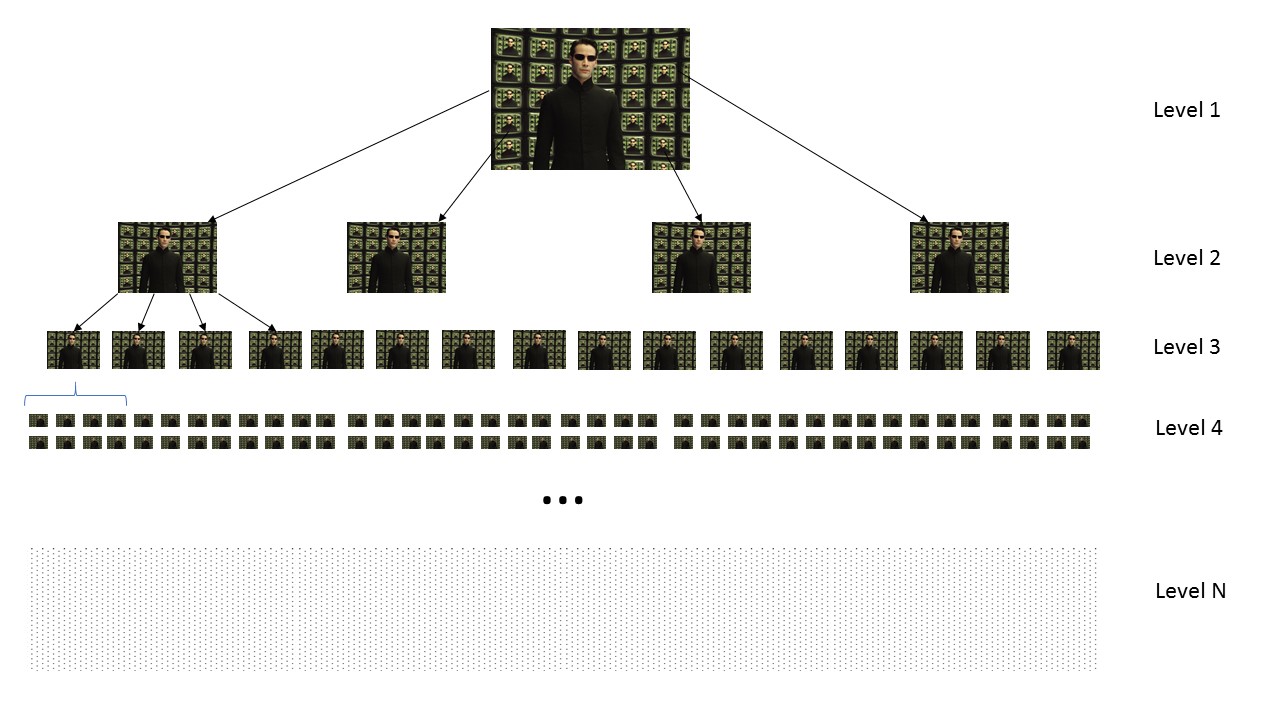

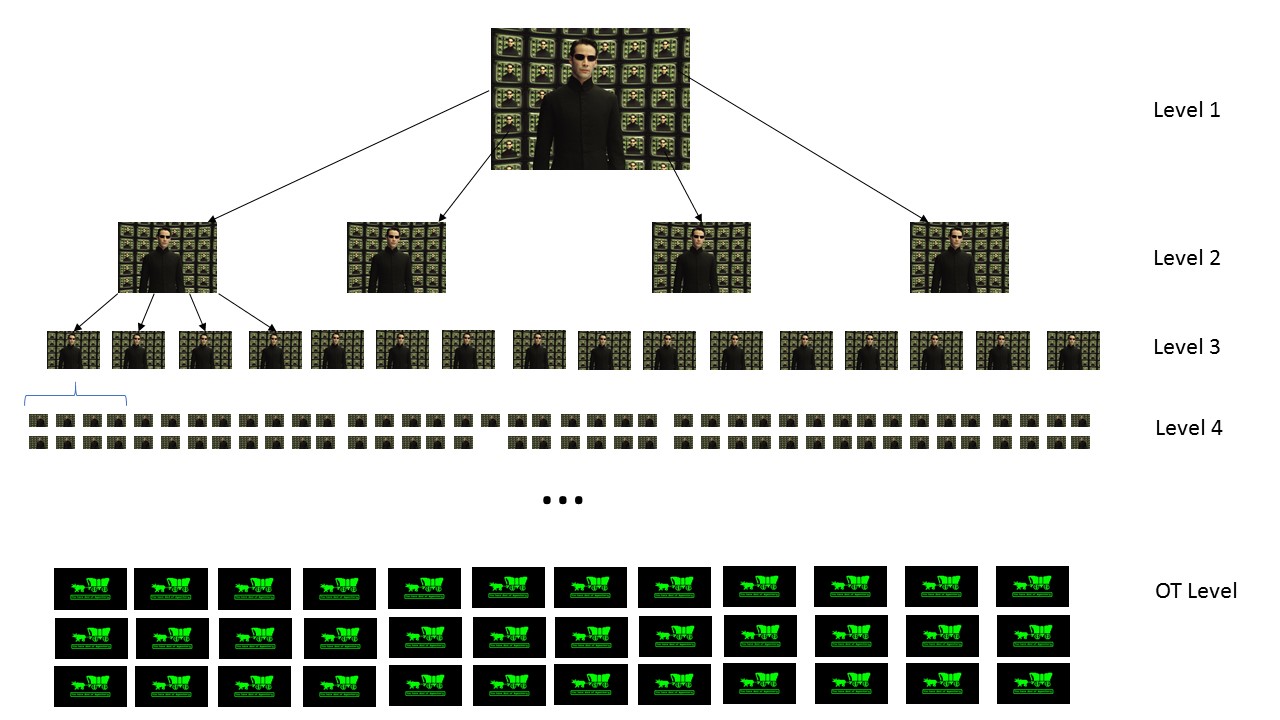

Simulations of Simulations: At Level 1 you have “reality” – Neo the actual human being. At Level 2 you have many simulations that are running on “real” computers existing in Level 1. Each simulation in Level 2 then runs simulated worlds of its own, creating many more simulations at Level 3, and so on.

4. Based on 3, we are now talking about a situation in which you have one “real universe” (what Musk calls base reality) and a gazillion “simulated universes.” (For example, in the picture above there are 4 simulations at Level 2, 16 simulations at Level 3, 64 simulations at Level 4, etc. And, clearly, 4+16+64+etc… = 1 gazillion.)

5. The odds that we just happen to live in the one real universe are, therefore, 1 in a gazillion.

6. Ergo, we probably live in a simulated universe. And by probably, I mean we can be 0.9999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999 percent confident that we are simulated beings.

This is the sort of argument you will often hear from pro-simulators like Musk. And admittedly it’s a rather convincing argument. You’ll hear a thousand variations of it—some admittedly much more sophisticated—but the underlying logic is similar and mostly rests on two ideas:

1.That you can simulate universes.

2.That your simulated universes can simulate their own universes, and those simulated universes can simulate their own universes, ad infinitum.

These seem like reasonable assumptions, as long as you don’t squint too much. But what happens if you do squint?

III. Can You Simulate a Universe?

Some people may object that even if you could simulate physics, chemistry, and biology, there are things that exist beyond what the laws of physics, chemistry, and biology dictate: souls, minds, patronuses. If you are one of these people you need not bother with what follows—you’ve already found your counterpoint to the simulation argument. Thanks for playing and here is your parting gift:

Other folks couldn’t care less about souls and other metaphysical things, but they still object under the pretense that you can’t simulate even something so “simple” as the laws of physics.

Actual physicists have waged proxy blog wars on this exact issue. Much of it rests on whether the universe is—at its core—continuous or discrete (i.e., singular). Computers are good at computing discrete things, but not continuous things. If the laws of physics are ultimately continuous in some fundamental way, it may be hopeless to try to approximate them using a computer that calculates with individual bits.

To be completely honest, I have no idea which side has the better argument here. These issues wade into cutting edge theories of how the universe is built at the most fundamental levels. The folks waging these thought wars have a much more comprehensive understanding of the cutting edge theories than I do, and even still, they can’t seem to agree.

Theoretical issues aside, is it practical to try and simulate a universe, or even some little part of a universe?

The problem is that it takes real-world resources (microchips, memory, power cables, etc.) to simulate stuff. The more stuff you want to simulate, the more real world resources you need to devote to the task. If you want to simulate an entire universe—including the earth and Tom Cruise and Alpha Centauri—you will need to build a supercomputer that is made of most of the atoms in your universe (or possibly more atoms than exist in your universe).

And that seems a bit…presumptuous. Sorry kids, we have to clear out this cancer ward because the scientists need all the atoms in this hospital for their universal simulation.

So, it’s unlikely anyone could perfectly simulate a whole universe, or even part of a universe.

On the other hand, the argument that we live in a simulation doesn’t necessarily require that the simulation is perfect. It only requires that the simulation works well enough to fool us.

For this latter point, consider some experimental evidence from the “real world.”

Here’s the original Grand Theft Auto:

Are those green things near the curb people or trees?

And here’s Grand Theft Auto V:

Is this a video game or footage from some dude’s GoPro? I’m stumped.

These advances in simulated carjacking took less than a decade. Imagine how far simulations could advance in the next 10, 100, or 1,000 years. After all, the proof doesn’t require that we can currently simulate a universe—only that it might one day happen.

Can you simulate a universe, or at least some small portion of a universe in an imperfect way? I’d give a strong maybe here. This doesn’t appear, to me, to be some tragic flaw in the pro-simulation argument.

IV. Can Your Simulation Simulate a Universe?

For me, there’s a more glaring problem with the simulation “proof.” Recall that the proof rests on the following idea:

That your simulated universe will simulate their own universes, and those simulated universes will simulate their own universes, ad infinitum.

Is this reasonable? I’m not so sure.

Remember even if you can simulate a universe in theory, it takes resources to do so. You very likely can’t simulate your whole universe, only some portion of it. But this same argument should apply to your simulation. That is, when the simulated you attempts to create her own simulation, she will only be able to simulate a portion of her own simulated world.

As you climb to higher level in the “space of all simulations” pictured above, the simulations must necessarily become less complex in some way.

And at some point, the simulation becomes too crude to simulate universes of its own. At least universes that have conscious entities that can worry about whether or not they live in a simulation. At that point you don’t get deeper levels of the Matrix, you get a bunch of virtual universes that are just complicated enough to play Oregon Trail.

Welcome to the Oregon Trail Level (the OT Level). Once you reach the Oregon Trail Level there’s nowhere left to go. You can’t simulate any further universes – though you can still do cool things like typing Y when prompted “You are now at the Kansas River Crossing. Would you like to look around? (enter Y/N)”

OK, so far, so good. The simulations get progressively less complicated until you reach the OT Level, but none of this would seem to be a problem for our pro-simulation argument.

Or would it?

IV. The Oregon Trail Paradox

In fact, the existence of the Oregon Trail Level throws a wrench into our proof, once we also recognize something about the distribution of simulations across the different levels.

Note how the number of simulations increases dramatically as you pass from one level to the next. In our example you started with 4, then 16, then 64, and so on. Each level not only has more simulations than the previous level, it has more simulations than all the other levels combined 1.

And so we arrive at our problem. The math works out such that we aren’t just likely to be living in any simulation, but we are very likely to be living in a simulation in the OT level.

OK… so what? Who cares what level we live in?

Well, the problem is that as we discussed above, the OT level is where you have simulations that are too crude to simulate any further universes.

But we started with the assumption that we could simulate universes. And ended up concluding that we (in all likelihood) live in a simulated universe where you can’t simulate other universes.

This is the Oregon Trail Paradox (don’t search for it on Wiki because I just made up this term for an otherwise well documented flaw in the pro-simulation argument). And when you have a proof that results in a paradox, well…

V. Full Circle

Where does all this leave us? Do we live in the matrix or not? I have no idea.

My goal here isn’t to try and convince you that we definitely do or do not live in the matrix. My goal is simply to demonstrate how these pro-simulation arguments being espoused by the likes of Elon Musk or Stephen Hawking aren’t as strong as they may appear at first blush. Of course there are probably more sophisticated pro-simulation arguments than the version I presented here that may get around these issues – but bear in mind with added sophistication comes new places for flaws to hide.

At this stage, you can probably believe we live in a simulation or not and feel like rationality is on your side in either case. In that way it’s a bit like politics. Just go where your heart leads you.

Footnotes

1 Note that this pattern of dramatically increasing numbers of simulations at each level happens so long as each universe simulates many universes, rather than say just one. If each universe only simulates one universe of its own (meaning there is just one simulation in each level), the probability part of the argument falls apart. Now you have reasonable odds of just existing at any level. Including base reality. In which case you are back to square one again.