Prompt Images

In recent years, one of the more abstract, but consequential, casualties in America was objective reality: facts and truth, long-clinging to their respective deathbeds, have finally been buried.

There are many reasons why this has happened. They are far too numerous to unpack here, and they are far too unwieldy for me to tackle intelligently. But like the railroad tycoons, Steve Jobs, and Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg before us, we can profit from explosive revolutions of technology and culture. We will succeed only if we recognize that this change exists, understand that it is irreversible, and adapt to it early.

In other words, we must learn how to lie, or we’ll get left behind by those who do it best.

Consider: At its heart, lying is about creating, maintaining, or reinforcing an information imbalance. In a world driven by information, such an imbalance is an advantage.

- Sometimes the advantage is avoiding punishment, like when you’re 5 and you swear that you didn’t break your parents’ lamp.

- Sometimes it yields profit, as when you tell your customers that something is free.

- And sometimes, it’s to make yourself feel better, such as when you tell everyone that you would have won the popular vote if not for millions of illegal voters.

The Age of Lying

The Information Age has been replaced by the Age of Lying, which poses a problem for those of us who have integrity; value science, fact, or objective truth; or are just not creative or mentally consistent enough to lie well. But worry not: there is hope.

An episode of the 2009 satirical sitcom Better Off Ted opens on a meeting scheduled by the title character Ted, the heroically too-just head of an R+D department at a multinational evil corporation. He’s brought two of his team of scientists to present their latest invention to their boss Veronica, a delightfully endearing sociopath. It’s a machine that sounds off with a loud buzz when it hears a lie… and it works flawlessly until Veronica steps up to the plate.

She casually tells the team that she hunts people for sport, that she’s poisoned one of the three of them, and that she’ll force the other two to have sex before the day is over. When the others start panicking at the box’s silence, she reveals that as she’s convinced herself those statements are true, the box has no power to detect the changes in her voice that normally accompany lies.

But unlike Veronica, you don’t need to be a sociopath to come out on top in this Age of Lies. Worry not, for I am here to help you lie by lying about lying: telling truth creatively. Let the awesome trio of logic, math, and language be your steeds in this brave new world as I share some of my best-kept secrets.

Onward!

The Lie by Omission

This technique is relatively easy, pretty straightforward, and will be recognized by anyone who spends time with politicians. If you never address a topic, then you technically can’t lie about it. When asked a question, simply speak about something else. Depending on the context, this could be a related topic, a question of your questioner, or in extremely specific cases, something non-sequitur. Examples:

Mr. Mayor, what is your connection to the recently arrested alleged serial killer who named you in his list of inspirational role models as “The Man Who Taught Me Everything I Know?”

“This man is an example of a poor, lost, and pitiable soul. May God have mercy on him.”

He reportedly had a diary in which the entry for the day before yesterday read, “Had a nice dinner with the Mayor. He told me the best places to hide the bodies now that the police patrols have been cut back.” Did you share that information with him?

“I campaigned on a promise to keep our streets safe from crime, but have only gotten staunch opposition from the City Council. Why do they hate our city so much?”

Mr. Mayor, the man has a photo album with about 20 pictures of you and him, smiling together, kneeling in front of gruesomely disfigured women’s bodies. In every picture, you’re both holding what appears to be the current day’s newspaper. One photo has you two together with a paper celebrating your inauguration, and in the photo you’re both making the same victory gesture as in the newspaper photo as well as making a truly vulgar gesture with the Key to the City you just received. Are you really denying this is you?

“Do you go around to your friends and family and ask these sorts of horrible questions? How would you like it if I showed up where you worked and started pestering you like this?”

Semiotic Switcharoo

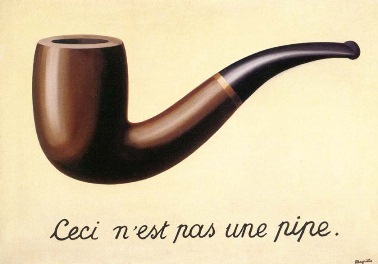

Language is an amazing thing when you really stop to think about it. According to Saussure, one of the founders of a field of study called semiotics, the concepts you have living in your brain are called the “signified.” If you want them to live in my brain too, you use a “signifier” (for example, a word) to communicate it to me. But the signifier and the concept are fundamentally different, a subtle point Magritte tried to address in his famous painting. Unfortunately, his patron didn’t quite “get it,” and the resulting disagreement about whether or not Magritte should be paid for the piece is actually one of the underlying causes of World War II.

“N’est pas une pipe,” you say? Well, ceci n’est pas une “real painting” either. Now get back to work and paint me something that has apples in a bowl. And none of that “Son of Man” crap either.

Since there’s a fundamental difference between what we say and what we mean, all conversations and communications are (at best) educated guesses as to what anyone is even meaning. Use this to your advantage—if people are lax in their use of poor definitions, then you should feel no shame in exploiting them. Just switch their (likely) meanings for yours internally before you reply.

Roommate: “Did you just eat the last cookie?”

<I’m fairly certain there are other cookies in the world, so no, that wasn’t the last cookie yet by my interpretation. Rather unusual assumption of him to make, that I could do such a thing. And it was more of a small cake, anyway. Plus I’ve only just swallowed it—surely I haven’t completely “eaten” it yet.>

Me: “No.”

Roommate: “Are you doing that game again where you overanalyze the meanings behind my words to lie to my face about something I literally just saw you do 10 seconds ago?”

<Well, it’s not really a game if no one wins, is it? And overanalysis is a bit of a stretch—it’s in the spirit of honest communication that I’m trying to make sure we’re all on the same page.>

Me: “No.”

Roommate: (punches me in the stomach)

The Flexibility of ∅ – A.K.A. The Empty Set is the Safest Bet

This is by far the most advanced technique because of its limitless application. And there’s only a little math (logic) involved. Stay with me—if you can master this one, you can lie tell the absolute truth with impunity.

First, consider what it means to make an assertion about a group of objects. Perhaps I want to make the bold claim that “every table has four legs.” Is this true? How would we know?

At first glance, you might think you need to find all the tables in the world and count their legs. Let’s say you decide this is a good idea and while you’re counting, you find the Lövbacken. You now know you can have a table without four legs (but you also now know that the distinctive grain pattern in the poplar veneer gives each Lövbacken a unique character). As soon as we find a counterexample, we don’t need to keep counting, because our original assertion was about every single table. One counterexample is enough to show the statement about the entire group is false.

What if the group has only one object? For example, “My computer is on right now.” I only own one computer, and I’m typing this on it, so it must be on. And sure enough, it is. The only way the statement could be false is if “on” doesn’t apply to the single computer in the group. Not really earth-shattering but… let’s take it a step further.

What about the statement, “Every table made out of pure gold in this room is also a computer.” How do we decide if this is true or false? Well, first I need to find out if there are any tables made of pure gold in the room. A quick look around says that there are not.

A table of pure gold. (I enjoyed the unironic combinations of phrases such as “My wife showed commendable & saintly patience,” “I had the tablecloth custom-made, using lavish amounts of fabric,” and “Have fun creating a Midas Touch Table of your own.”

In math, a group with no objects in it–such as the group of tables in my room made of pure gold—is referred to as the “empty set,” symbolized by ∅. And like the statements above, we evaluate truth statements about the empty set the same way as other groups: by checking to see if there are any items in the group that act as a counter example to the statement.

But there are no items in the group. So I can’t show that they’re not a computer. I can’t show anything about them—they don’t exist!

Therefore, my statement must be true.

Interestingly enough, the statement “Every table made out of pure gold in this room is not a computer” is also true for the same reason. In fact, I can say whatever I want about tables made out of pure gold in this room, and it will still be true. It turns out any statements made about the empty set are true.

Bingo! All you have to do is phrase any of your statements so they’re referring to empty sets, and you’ll be in the clear.

- “The restaurant just called—they overbooked the reservation I had for our anniversary dinner tonight.” (Never made a reservation.)

- “The homework I finished this morning got corrupted when my hard drive died.” (Didn’t do my homework.)

- “My girlfriend and I went skiing last weekend.” (Single.)

- “I’ve really been seeing amazing results with my exercise routine.” (Routinely don’t exercise.)

- “You’re even more stunning than the last time I remember seeing you all dressed up like this.” (Can’t remember what I had for breakfast let alone what other people used to wear.)

Lying, For the Win!

There you have it: just a few of the ways I lie my way through life without ever really lying. Use at your own risk.

If you make a rookie mistake and get caught in a lie you from which you can’t escape, even with semantic contortions, or else succumb to an ever-growing pit of nihilistic despair when you realize that nothing can be objectively evaluated…

I’ll deny ever having shared this with you.

And mean every word of it.