Prompt Images

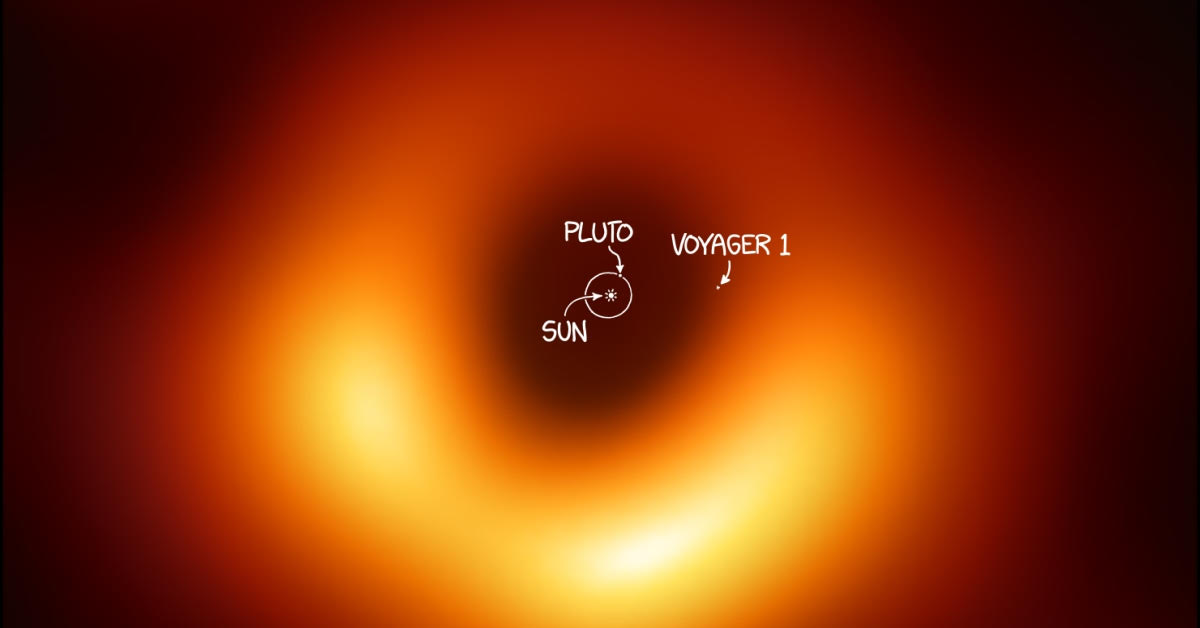

You may recall that last April the scientific world—and Twitter—went bananas for several days after we got our first ever photograph of a black hole. In case you were living under a rock, here’s that photo:

I know, I know. It’s a bit—grainy. But it’s a photo of an actual black hole from about 53 million light years away that required an enormous amount of scientific work to achieve, so maybe just save the scoffing for your Instagram feed.

In any case, the thing that boggled my mind more than anything about this particular black hole—referred to as M87*—is its unfathomable size. This thing isn’t the size of a star, like our sun. It isn’t the size of a dozen stars.

So how big is it?

See that dark part in the middle?

Our entire solar system could fit in that space, with plenty of room to spare. Have a look for yourself:

Of course, like players on the Houston Astros, black holes come in many different sizes. Some black holes have masses equal to a dozen of our suns. By comparison with these black holes, M87*—clocking in at around 2,400 billion suns—these former black holes are downright lilliputian.

According to the usual model for how black holes form there’s a minimum size to a black hole.

In this model, caused by the implosion of stars, you need to start with enough mass for gravity to become so strong that it can overcome all the nuclear forces in matter that normally act to keep an object’s atoms from collapsing in on themselves. If a star’s mass is less than some critical value, it won’t implode when it dies. It will just turn into a lump of star coal.

But many physicists believe that there may be other ways to create black holes that has nothing to do with stars.

To make a black hole you just need to force a TON of matter into a really small volume. Stars are an obvious choice because they are so massive. But another idea is that perhaps—and this idea is still rather speculative—black holes could have formed in the early universe, right after the Big Bang, when everything was crazy hot and crazy dense (i.e., a lot of mass within a given volume). The formation of such black holes, dubbed “Primordial Black Holes” (or PBHs) by the two soviet physicists who came up with the idea, would have nothing to do with stars.

Because you don’t need to start with a star to make a PBH, it’s possible to make black holes that are relatively small.

How small could a Primordial Black Hole be?

Stephen Hawking once estimated that they could weigh as little as 0.000000001 kg. Such a black hole would be unfathomably tiny. Almost too tiny to be interesting.

Okay, but these are hypothetical objects. No one has ever observed one. How seriously do scientists even take the idea of “tiny black holes”?

Several years ago some scientists proposed the idea of a new massive object, which they dubbed “Planet 9” (since Pluto’s demotion to mere asteroid, there are only 8 planets in our solar system). The idea is that Planet 9, if it exists, might be the cause of strange gravitational anomalies in the orbits of objects in the outer reaches of the solar system.

Just recently, a pair of physicists put a draft paper online with the provocative title What if Planet 9 Is A Primordial Black Hole?

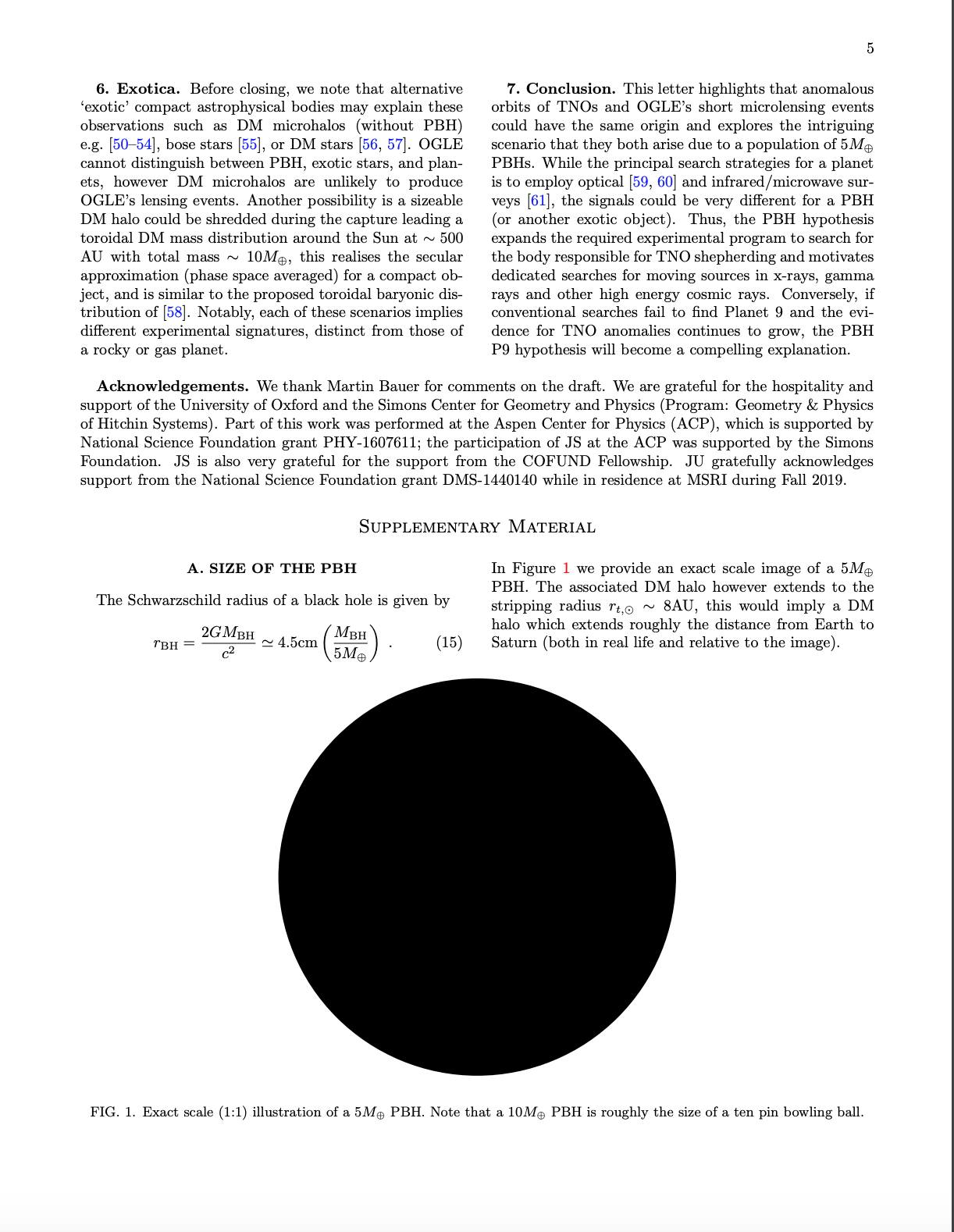

In this paper (yet to be published in an actual journal), the authors argue that a primordial black hole with a mass of 5 to 10 times that of Earth could explain the gravitational anomalies in the data. Being black holes, it would also explain why no one has yet to actually “see” Planet 9.

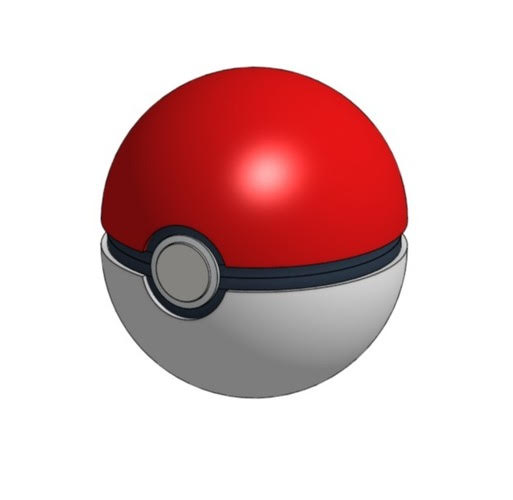

So just how big is a black hole that weighs, say, 5 times the mass of Earth? Because black holes famously pack a lot of mass into a (relatively) tiny package, the math works out so that the diameter of this black hole is about 9 cm, or 3 ½ inches.

Basically, this black hole would be the size of a Pokeball.

In other words, you could hold this black hole in the palm of your hand. You know, assuming you had no concern about putting your hands near a region of space where literally nothing that crosses the boundary can ever escape. And no concerns about trying to hold something that weighs as much as five Earths.

One of the coolest parts of their paper is that they included a graphic indicating the size of the black hole. As you can see for yourself, the black hole is shown with its ACTUAL SIZE (“Exact Scale (1:1)”). How often does that happen in an astronomy paper?

For scale, the hypothetical black hole takes up 1/3 or of a standard sheet of paper.

To be clear, this is a highly speculative idea. No one is suggesting there definitely is a 3 inch black hole floating around the edge of the solar system. But it’s an idea. And a fun one, which apparently may be testable, according to the authors of the yet-to-be-published paper.

So yeah, it’s possible that there are tiny black holes floating around out there in the universe. Pint-sized pockets of spacetime with enough gravity to keep a moon in orbit around them.

Not a bad upgrade from Pluto, no?